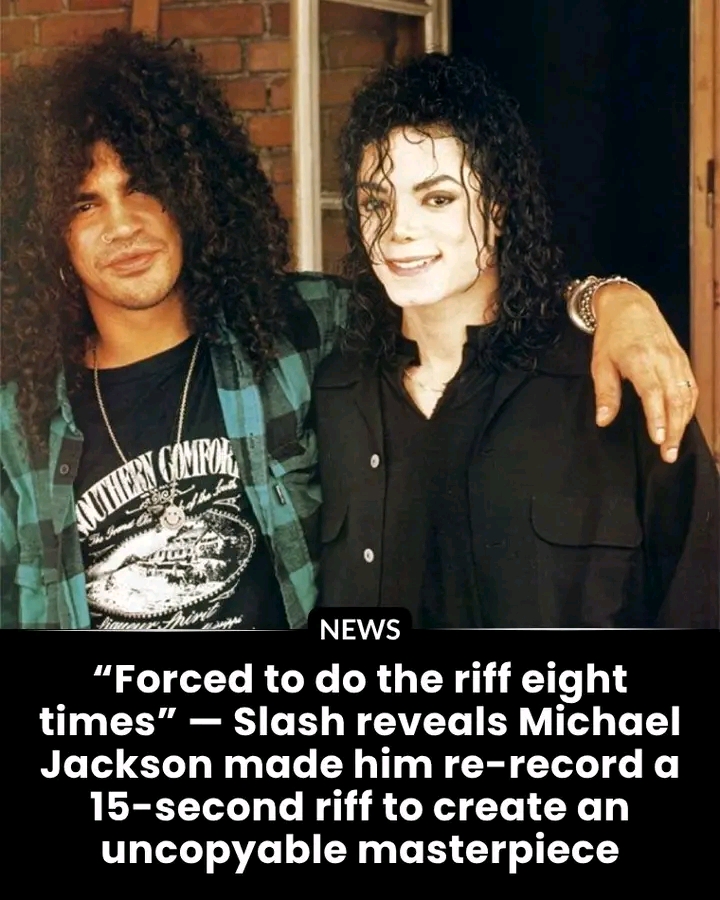

Slash had been tapped to play guitar on Jackson’s 1991 album Dangerous, a project where Jackson was pushing into harder rock territory. The two men met at the studio — Jackson, larger than life; Slash, the blades-and-top-hat shredder who normally lived in the world of high-volume rock. Slash recalls:

So I called him back and he wanted me to play … We made a date and I went down to the Record Plant in Hollywood… He was there with Brooke Shields. That was very surreal.”

But once the session began the atmosphere shifted — not into effortless collaboration, but into a grind of trying to capture something dangerous.

Slash later admitted the working style with Jackson “wasn’t what you’d call true collaborating… Mike just does his thing… and he just let me do my thing.” That sounds easy, but the actual process was anything but.

The riff and its eight takes

The story goes: Jackson listens to the first take of the riff. He stops it.

“It’s not dangerous enough.”

Slash starts again. The same riff, iron-tight, but again it’s cut: “Not dangerous enough.”

This happens again and again — take after take. By the eighth time, frustration is creeping in. Slash knows his chops, knows his tone, knows how to shred — yet Jackson is rejecting it.

What is “dangerous enough” in this context? It isn’t just technical precision or volume. It’s attitude. It’s a vibe. Jackson was chasing a moment where the guitar doesn’t just support the song — it threatens, it looms, it hurts a little. He wanted that raw edge.

Finally: Jackson walks into the booth. He begins to dance, rhythm pulsing, energy shifting. Slash locks eyes with him, the groove tilts. Now the riff breathes, snarls. The eighth take clicks. The danger is there. The fire is there. Something unrepeatable is captured.

The result: one of pop’s boldest rock moments

That take became part of “Give In to Me,” one of the heavier cuts on Dangerous. The track is described as a “hard-rock and heavy metal ballad” and features a blistering lead from Slash.

In a time when Jackson was known mostly for pop and dance, this was him reaching into darker rock terrain — with Slash as his weapon. The raw intensity of that guitar didn’t just accompany Jackson’s vocals; it elevated them into something more urgent, more visceral.

Why it matters

Cross-genre collision: Two worlds colliding — pop and rock — and in the collision, something transcendent.

Art-meets-instinct: Jackson didn’t ask for perfect, clean; he asked for danger. That kind of artistic demand isn’t common.

Fire moment vs routine take: Countless artists cut dozens of takes. Few chase the edge so explicitly that the moment of breakthrough becomes part of the myth.

Uncopyable magic: You can imitate rhythms, mimic tone, but you can’t replicate the exact studio mood, the exact interplay of dancer and guitarist in that moment.

How the story inspires

For musicians, producers, creators of any kind: the story is a reminder that great art often demands the uncomfortable. Jackson didn’t settle for “good”—he wanted “dangerous.” He forced the riff out of comfort zone. Slash, though a rock legend, still had to dig deeper.

In creative work: there’s the routine take, and then there’s the one where you feel the hairs on your arms stand up. That’s the eighth take. That’s the moment where frustration flips into fire.

Final thought

Picture this: A studio bathed in half-light. Jackson, in signature moonwalk mode paused, watching. Slash, top-hat off, Les Paul glowing. Riff loops one last time. Stop. Jackson nods. He moves. The groove changes subtly. Slash plays. It burns. The eighth time. And what was simply a riff becomes a signature moment.

In pop history, many riffs are memorable — but few were made under such deliberate pressure. And fewer still were the product of a pop titan demanding danger from a rock hero. The next time you hear “Give In to Me,” remember: it wasn’t just a tak

e. It was take number eight, when frustration turned into fire.

Leave a Reply